Publisher’s description: “The stories of lived experience offer powerful representations of a nation’s complex and often fractured identity. Personal narratives have taken many forms in American literature. From the letters and journals of the famous and the lesser known to the memoirs of former slaves to hit true crime podcasts to lyric essays to the curated archives we keep on social media, life writing has been a tool of both the influential and the disenfranchised to spark cultural and political evolution, to help define the larger identity of the nation, and to claim a sense of belonging within it. Taken together, individual stories of real American lives weave a tapestry of history, humanity, and art while raising questions about the veracity of memory and the slippery nature of truth. This volume surveys the forms of life writing that have contributed to the richness of American literature and shaped American discourse. It examines life writing as a rhetorical tool for social change and explores how technological advancement has allowed ordinary Americans to chronicle and share their lives with others.”

Purchase at Routledge, Amazon, and anywhere books are sold.

SOLD OUT!

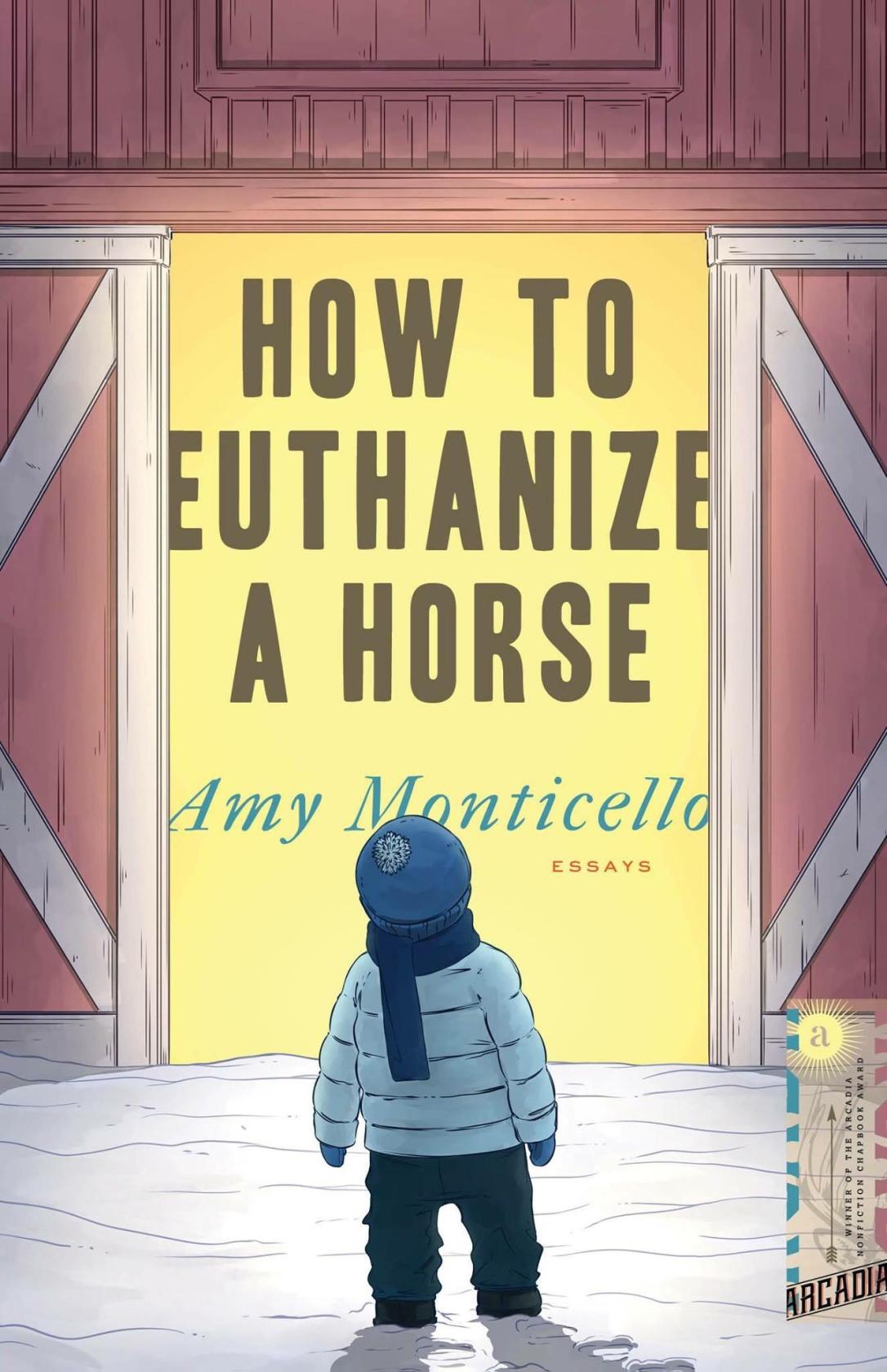

In six essays written after the death of her father, Monticello carries grief toward the life that comes after. From that vantage, she looks clearly at her father, her mother, herself, her pregnancy and new motherhood, and an actual horse to find the interconnectedness of love and shame, and the fraught, ongoing things that persist through loss, that are changed by it, that are made by it.

Praise for How to Euthanize a Horse

“Amy Monticello dives into the depths of loss to retrieve the hard-won pearls. She maps the ways in which the lamp of grief and memory itself casts a glow with which to move forward into the darkness.”

—Sonya Huber, author of Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and other Essays from a Nervous System

“Monticello fights loss by showing us what it means to be alive. After losing her father, she doesn’t back away from pain and grief; instead, with a tiny flashlight, she walks through it, resuscitating all that was thought to be dead along the way: old boyfriends, pets, and memories so powerful they’re bursting through the page. The book is heartbreaking and vulnerable and nothing short of magical.”

—Liz Scheid, author of The Shape of Blue: Notes on Loss, Language, Motherhood & Fear

“Monticello’s How to Euthanize a Horse is a powerful meditation on death, mourning, and moving on not from, but with, the burden of grief. This is a searing, intimate collection of lyric, unsparing essays that demonstrate the best of what first person creative nonfiction can do… let us live, for a moment, in someone else’s skin.”

—Sarah Einstein, author of Mot: A Memoir

Close Quarters reaffirms that love doesn’t always end when a marriage does. In the acrid haze of smoke and alcohol, this broken family repair their seams, indulge nostalgia, and examine the hurt that even love can’t prevent.

Praise for Close Quarters

“Amy Monticello’s Close Quarters is a family portrait mixed from spirit and grit, from tenderness and longing, from the small graces beyond ruin and loss. The essays in this chapbook contemplate the evolution of love. This is a book about finding beauty and redemption where we can; it’s about the ties that bind. Close Quarters moved me greatly with its story of a mother, a father, a daughter–this family that endures.”

—Lee Martin, author of From Our House

“Amy Monticello’s short vignettes about her family and her father’s bar are wonderful. They resist the labels we try to put on ourselves, on marriage, on good and bad behavior, instead delving into what it’s like when alcohol and difficult situations tear a family apart, yet still somehow bind them together. Her characters are so human, her clear-eyed romanticism and lovely prose so compelling, that Close Quarters is hard to put down. Instead, you underline phrases, dog-ear pages, just so you can go back and see how someone perfectly captured an emotion, a scene, a moment, or some other thing you couldn’t have said better yourself.

—Rebecca Barry, author of Later, at the Bar